WARNING: This report includes a photo of a deceased goose.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has identified a highly transmissible strain of avian flu in multiple samples obtained in southern Manitoba, following an extensive bird die-off event as described by researchers.

During early December, approximately 500 bird carcasses, predominantly Canada geese, were discovered near water bodies in southern Manitoba. While clusters of dead birds were also found near the Red River north of Winnipeg’s Perimeter Highway, the most concentrated group was located in ponds in Niverville.

Biologist Frank Baldwin from the Canadian Wildlife Service informed CBC News that bird samples were sent to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency after testing positive for avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu, to ascertain the specific strain.

A spokesperson from the federal agency disclosed that on December 11, 39 wild bird samples were forwarded to the National Centre for Foreign Animal Disease for analysis. The laboratory results confirmed that 38 of the samples were positive for the highly pathogenic H5N1 strain of avian flu.

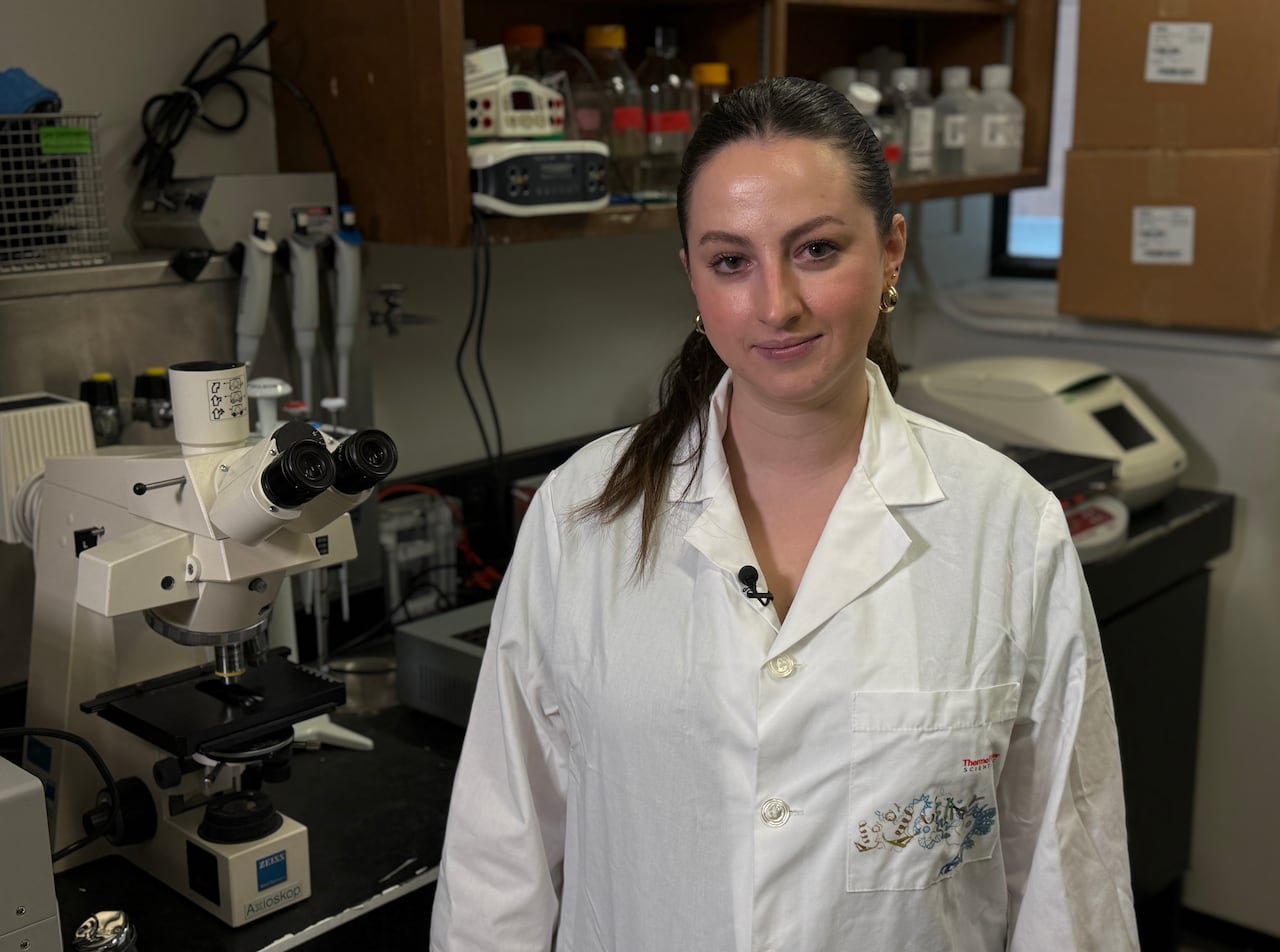

University of Manitoba researcher Hannah Wallace, an expert in viral immunology, expressed relief that the samples tested positive for the known H5N1 strain, which causes substantial illness and mortality in birds. Wallace had concerns about potential mutations of the virus into a more dangerous form for both avian species and humans.

Although cases of H5N1 have been reported in humans, the concern is the potential creation of a hybrid virus with combined avian and human origins, posing increased risks to human health.

The identified H5N1 strain in the collected samples is prevalent among domestic poultry and wild bird populations in North America, according to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. Wallace emphasized that this finding was as anticipated, as it aligns with previous experiences.

Avian influenza was initially detected in Canada in late 2021, with many birds in the country already exposed to the virus, providing some level of existing immunity, Wallace explained.

Weaker or undernourished birds may be more vulnerable to contracting H5N1, especially if they lingered in southern Manitoba due to unseasonably mild weather, facing food shortages and cooler temperatures.

Environmental Persistence

Studies indicate that avian influenza can endure in the environment even after birds have migrated for the season, Wallace noted. While the presence of the virus in the water where the dead birds were found last year is unlikely, it could persist in ponds or river sediment, surviving through winter until spring.

Baldwin of the Canadian Wildlife Service highlighted the variable behavior of avian influenza annually, with some bird populations having sufficient antibodies to combat the virus. However, the duration of this protection remains uncertain.

Anticipating mortality among snow geese and Ross’s geese during their migration through Canada in April and May is likely, Baldwin added.

Avian influenza has posed challenges not only for scientists but also for poultry farmers in Manitoba over the years.

Rod Wiebe, the board chair of Manitoba Chicken Producers, emphasized the virus’s contagious and deadly nature, making it a significant health concern. While enhanced biosecurity measures can aid in prevention, controlling bird flu transmission from wild birds remains challenging, particularly during peak periods in fall and spring migration.

Candace Lylyk, owner of Breezy Birds Farm in Morris, Manitoba, expressed her worries about wild birds potentially transmitting the virus to her poultry farm. Implementing strict protocols to prevent contact with wild birds has become essential for farm operations to safeguard against the threat of av